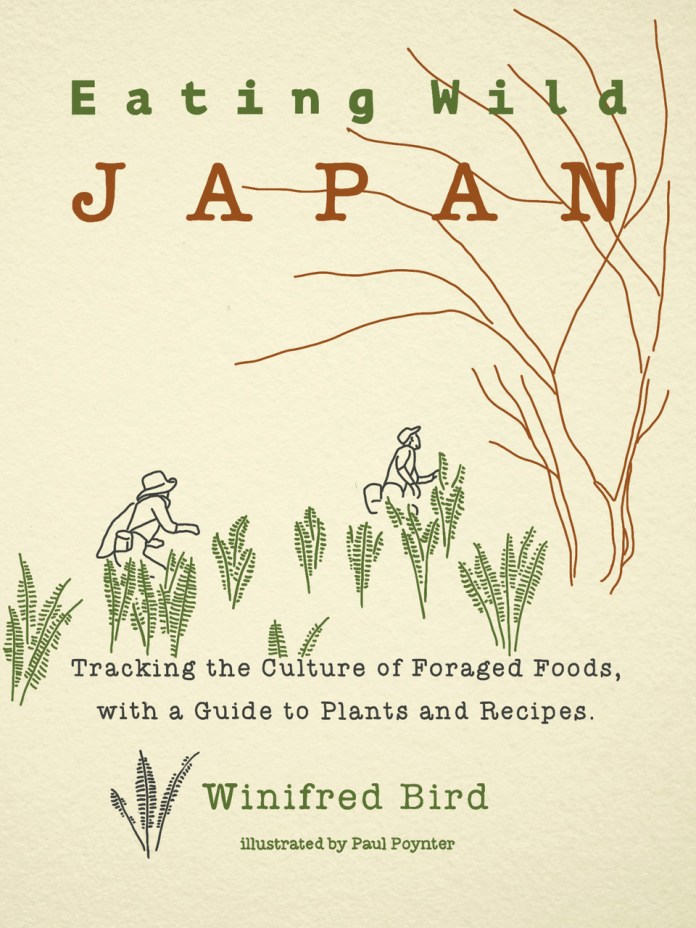

Eating Wild in Japan

Winifred Bird wants you to eat outside. While this admonition may not seem odd (who doesn’t love a picnic, after all?), Bird, the author of Eating Wild Japan: Tracking the Culture of Foraged Foods, with a Guide to Plants and Recipes (Stonebridge Press, 2021) has something more literal in mind.

“This book is very much about humans as part of the natural world and our relationship to it,” says Bird. “Now, it is so much more fun to go somewhere because I am constantly looking for plants I can eat. It makes me feel much more connected to the places I go.”

Bird’s first introduction to the world of sansai (mountain vegetables) was at the table of a neighbor over a shared pot of tea in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture. Subsequent visits featured an ever-changing sansai menu “always perfectly tuned to the turning seasons,” she writes. As Bird talked and ate and the friendship bloomed, she realized that in rural Japan these wild foods were commonplace. It began a subtle shift in her thinking and way of seeing the world.

“I started thinking that when people are eating and using a plant, they protect it over the centuries and have a reciprocal relationship with it,” she says, “It’s a sort of nurturing one another through time. When that relationship falls apart, though, oftentimes the plant meets an unhappy fate as people lose their stake in it.”

This sense of reciprocity captivated Bird along with the simple delicious foods she and her neighbor shared. She first learned of this give and take between humans and the environment through the the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer, a scientist and an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawami Nation. How, she wondered, had these plants shaped the culture and cuisine of Japan? What did they say about people’s relationship to the land?

Searching for answers to these questions propelled Bird into the mountains and forests and even along Japan’s rocky shores to forage alongside those still practicing these skills and maintaining this ancient relationship. The result is a richly woven depiction of the social, culinary, economic and natural history of Japan that these plants represent.

“When I worked as a journalist, I often had to define things in terms of economy or art or the environment,” she says, “but those divisions don’t reflect the world as it actually exists. All these things are completely integrated, and you can’t understand any of them without understanding the others. So, I wasn’t interested in just botany. I was interested in the relationships between people and plants.”

Like every relationship, though, Bird also found that sansai provided more than bucolic forest walks or delightful nibbles on Heian Period warabi (bracken fern) mochi. These plants allowed people to survive famines or fickle weather that dictate mountain life. To that end, a countless array of wild plants were managed, fostered and eaten for thousands of years throughout the seasons to ensure food security.

“Having a culture that values—and is dependent on—wild foods drawn from its own ecosystem over the course of hundreds and thousands of years, where people actually have to sustain it, encourages them to value diversity. You have to have a variety of things through the seasons in different habitats.”

While Bird acknowledges she only covers a small fraction of the plants available, she hopes the recipes in each chapter and the guide to 25 of the most easily found sansai inspire readers to eat, ponder, and see their environment in a new light— not as something separate but a world they are part of and have a deeper relationship with than even hiking, skiing or surfing.

“Food is so much more than a hobby, something to entertain ourselves with,” Bird says. “By being aware of where we are and eating locally like this, we have a stake in protecting the land and maintaining its diversity. I hope my book will make people think not only about Japan, but also how we relate to land, use and interact with it.”

Eating Wild in Japan