A brief cultural history of the sento from a hot water nut

I guarantee I go to the sento (public bathhouse) more than you. I know it’s not a contest but, if it were, I would win. I feel the overwhelming need to share my obsession.

Historians date the first public sento to around 1266. An 80-cm. entryway to a mixed bath led to a dark cave containing a pool of hot water. Bathers cleared their throats in order to let their location be known, although this custom bears no relation to the oji-san hacking on the stool next to you today.

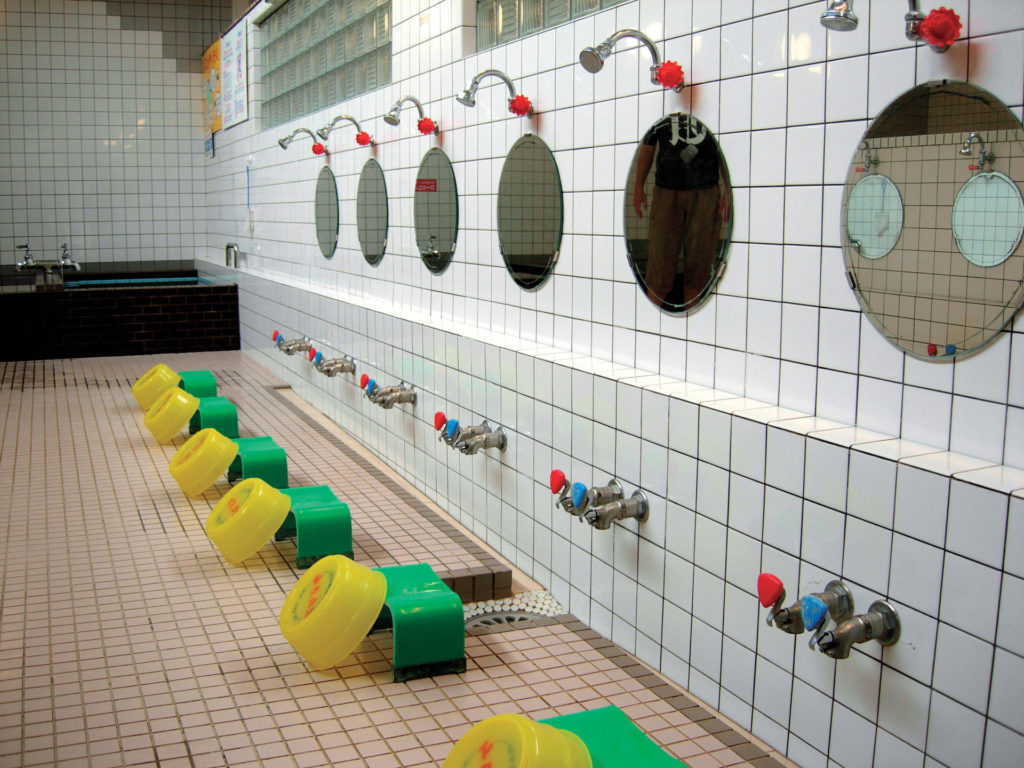

On Sept. 1, 1923, fires from the Great Kanto Earthquake burned almost all of the traditional wooden sento in Tokyo. When they began building again, it became a nationwide standard to use ceramic tile for the purpose of function and safety. Patrons immediately began throwing out their backs on the slippery surface.

Fast-forward to 1970, the peak of the small sento. In the aftermath of WW II, Japanese flocked to the baths to re-root themselves in their long-standing convention. However, as bathing facilities in private homes became common, the popularity of sento declined.

Culture also changed, and young people suddenly felt self-conscious about having their clothes off in front of others. I recently wrote to a friend and former ex-pat sento junkie now back in the U.S., to let him know the price of several of our favorites had gone up another ¥10.

He replied, “Did anyone under 80 notice?”

Why sento?

The Japanese language contains several expressions for interaction while bathing, most notable of which is “Hadaka no tsukiai,” referring to new friends made at the bath. Some of the first real conversations I had in Japanese were with guys I met in the sauna, where there is nothing to do but talk about sweat and baseball. This often led to a beer.

There is also an English-sounding katakana word for “skinship” that refers to becoming closer with those you already know through naked interaction. While most of us do not have the time or the money for an onsen getaway every weekend, a great way to compare notes from Friday night is a Saturday morning sento. It is just as relaxing and just around the corner.

If you are a foreigner at a sento, children under 8 are required to stare at you for at least one full continuous minute. OK, so I made that up. But 8 is in fact the standard cut-off age for children to enter the bath of either gender. There has been debate about this for decades.

Some argue that exposure to the opposite anatomy is detrimental to a child’s development, while others feel that “skinship” is key to becoming a socialized Japanese citizen. While I am a regular sento-goer, I have no opinion on the issue other than that I appreciate when children keep the screaming to a minimum.

Special Features

The ceilings of most sento are high, usually more than three or four meters, but the wall separating the men and women is often just over two meters. A tall foreign man was arrested in 2001 for staring into the other side even after women yelped and splashed him. Resist temptation.

Similarly, sento still standing from the post-war years might have a hole in the wall adjoining the men’s and women’s bath. The purpose? Sharing soap, of course. Before the boom, families often did not have enough money for more than one bar per family.

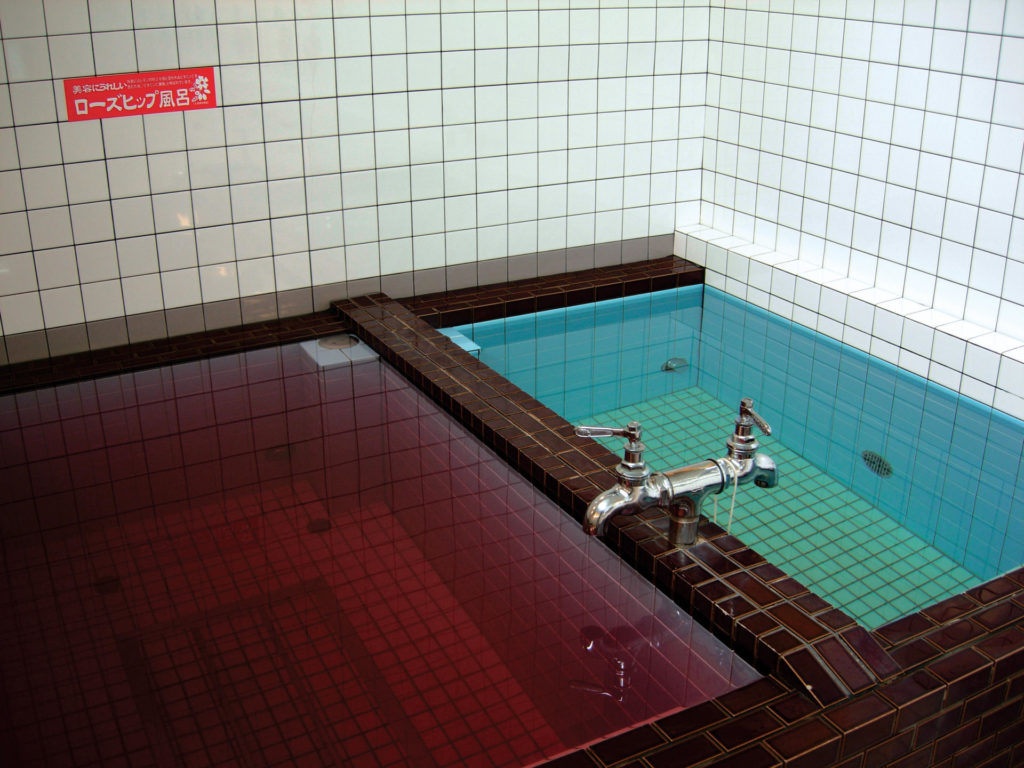

There is often no barrier between the bath and the datsuijo (changing room) in Okinawa sento, mainly because it is so hot, there is no need to keep the heat inside with the bathers. Osaka was historically known for its shallow pools and mushiburo (steam baths). The Tohoku area has more mixed-gender sento than anywhere in the country.

Repeated instances of disrespectful behavior by Russian sailors in Otaru, Hokkaido, led many small sento to ban non-Japanese customers altogether. Three foreign men, one of whom was a naturalized Japanese citizen, sued and won. Tension still exists in some places, but it is decreasing. I’ve been in several sento in Otaru and never encountered a problem.

Supersize Me

Sadly, small corner sento, the grimy tile kind with a few broken showerheads and one deep hot bath, are closing in droves. But the custom of public bathing will survive, for two reasons.

The first reason is the “super sento.” In the last 10 years, these large developments have begun to pop up everywhere. In addition to bathing facilities, they offer food and drink, foot reflexology, game rooms, pachinko, large tatami areas for eating and resting—even 15-minute barber shops.

They appeal to the whole family and are quickly gaining popularity. They are bringing back the bath as more than just a bath. It is a meeting place, a community center.

The other reason is what keeps me coming to the baths. Somewhere between the rotenburo and the sauna, I manage to forget I have a job, a deadline, and a life—even on a Wednesday evening.

Some argue they are too busy to take that much time for their ablutions on a daily basis, but I would say that is the very reason to do it. Japan is a fast-paced place. Somewhere in the rush we need a haven without having to escape the city.

While I was sitting in a sento with a friend the other day, he leaned back in the hot water and closed his eyes, the utter relaxation obvious. After a moment, he turned to me and said, “Man, I don’t do this enough.”

“Why not?” I countered.