Curling athlete Sayuri Matsuhashi’s journey to the top of her sport is an inspiration to deaf athletes and women juggling their roles as mothers while also pursuing their professional dreams.

A low grumble and sounds of furious scrubbing fill the ice rink, followed by a solid thunk and cheers. In the world of winter sports, curling gracefully glides onto the icy stage, where precision, teamwork and the artful sweep of a broom converge in a game that challenges the traditional boundaries of athleticism.

One athlete stands out, not only for her prowess on the rink, but for overcoming barriers that transcend the game itself. Meet 28-year-old Sayuri Matsuhashi, a national level curling athlete who has been deaf since birth. In a sport where communication is as crucial as strategy, Matsuhashi defies expectations proving that the universal language of dedication and skill knows no bounds.

Born in snowy Aomori in northern Tohoku, Matsuhashi is no stranger to winter sports. When curling was introduced in the American Winter Deaflympics (an elite international competition for deaf athletes), the then-12-year-old Matsuhashi and her father and brother, all non-hearing, were inspired to give it a try. Curling seemed fun, and it looked like a sport Matsuhashi’s father could continue to play even in his advanced years. The sport strengthened the trio, even during a painful period in their lives when Matsuhashi’s parents divorced.

Matsuhashi continued curling through boarding school, participating in her first beginner’s tournament in her second year of middle school. In her 20s, she moved to Kanagawa for work yet curling was a refreshing escape from her day-to-day life.

Curling is played between two teams, each comprising two or four players. The objective is to slide heavy granite discs, known as “curling stones,” toward a target area that is segmented into concentric circles. The players use brooms to sweep the ice in front of the stone, influencing its speed and direction. The ultimate goal is to position the stones strategically within the scoring circles, earning points based on proximity to the center.

Even though it looks simple, curling requires physical strength and endurance while engaging the mind, due to its long duration of play. It’s challenging and Matsuhashi is constantly learning. She even credits curling as a cure to her morning sickness when she was pregnant.

Today she lives in Tokyo with her husband and toddler, working as a sign language instructor while training for her next competition whenever possible. The working mother is faced with a challenge. While she and her husband are deaf, their daughter is hearing, otherwise known as “CODA,” or child of a deaf adult. As a result, their child is fluent in both Japanese and Japanese sign language.

“My parents are deaf, so I was raised in a non-hearing environment at home. So when my daughter was born, I was really surprised!” says Matsuhashi.

In 2021, Matsuhashi and her brother started competing professionally in mixed double curling competitions to prepare for the following year’s national Japan Curling Championships.

“While the basic techniques are the same as four-player teams, I think mixed doubles might be less challenging as there are fewer people involved,” explains Matsuhashi. That’s not to say that it’s easy, because the duo have to communicate concisely and quickly on the rink with both hearing and non-hearing people. It was a learning experience for her as she was unfamiliar with certain curling terms.

After winning a regional tournament, Matsuhashi and her brother became the first deaf people to qualify for this championship. Although they aimed to compete in 2022, it was unfortunately cancelled due to the pandemic. However, they went on to Banff, Canada for the World Deaf Curling Championships and came in second.

“Ukraine placed first; this was just when the Ukraine-Russia war broke out. It must have been an uncertain time for them, and they couldn’t even get uniforms, but the focus and determination they put into the game was inspiring,” says Matsuhashi in awe.

This year, Matsuhashi has her eyes set on entering the 2024 Winter Deaflympics in Turkey, taking part in two events: the women’s four-player team and mixed doubles.

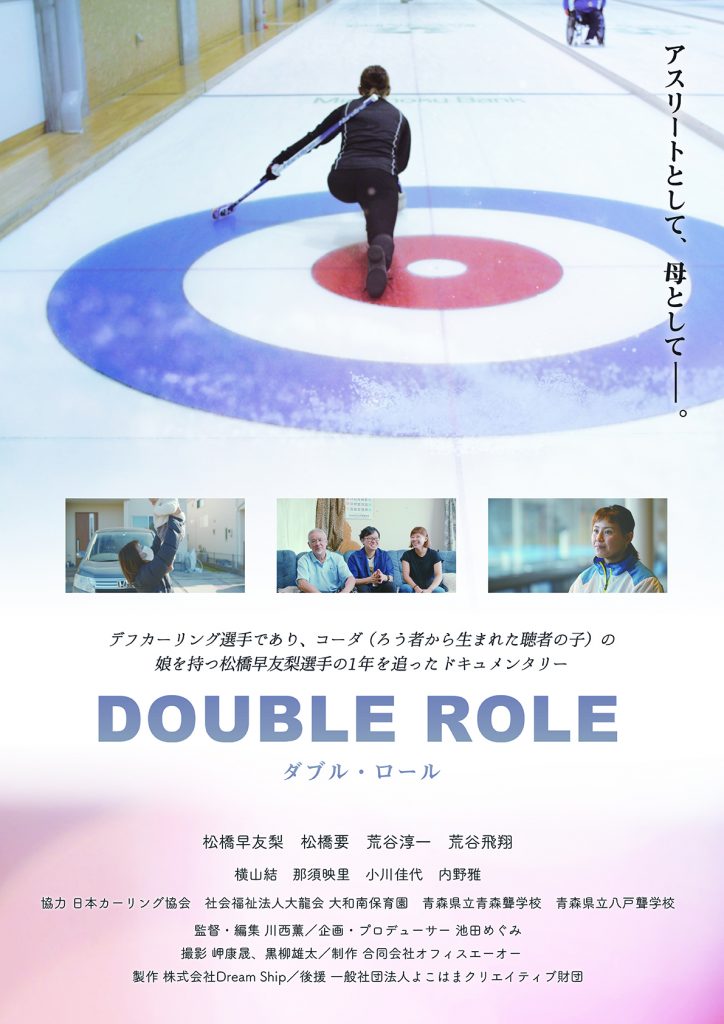

Matsuhashi’s successes are an inspiration to the local deaf community, even inspiring a documentary called Double Role that was released in 2023. In curling jargon, a double is a takeout shot in which two other stones are removed from play. A roll is the movement of a stone striking another. The aptly named title incorporates these terms while signifying Matsuhashi’s dual role as both a mother and deaf curling athlete.

“I had worked on a film with hearing and non-hearing staff prior to this, and was learning about the history of deaf people in Japan at the Kyoto Prefectural School for the Deaf,” says producer Megumi Ikeda. “Initially I wanted to make a film that followed the life of someone who couldn’t hear.”

After receiving numerous applications, Ikeda was drawn to Matsuhashi’s spark and personality. “The film was going to be about Matsuhashi raising her hearing daughter, but then I found out she’s this curling athlete as well!”

Filming during the pandemic was a challenge as shoots were constantly cancelled. However it was especially rewarding to Ikeda as she gathered an all-female team to make the movie. The project took a year to complete, but has been met with positive reviews, winning several awards and even premiering at the Yokohama International Film Festival. While unavailable online, the film continues to be shown at several theaters throughout Japan. Learn more here.

Matsuhashi hopes that awareness will be raised through all this. “There is an increasing number of deaf athletes, but unfortunately, many people don’t know about the Deaflympics. As a result, the support is relatively low compared to the Olympics and Paralympics, so I hope to spread the word about it,” says Matsuhashi.

“In Japan, there are places where sign language laws have been enacted, but actual changes are still limited and there is inadequate information and accessibility for hearing impaired people. Change will take some time, but it’ll make me happy if everyone can learn even simple sign language!”