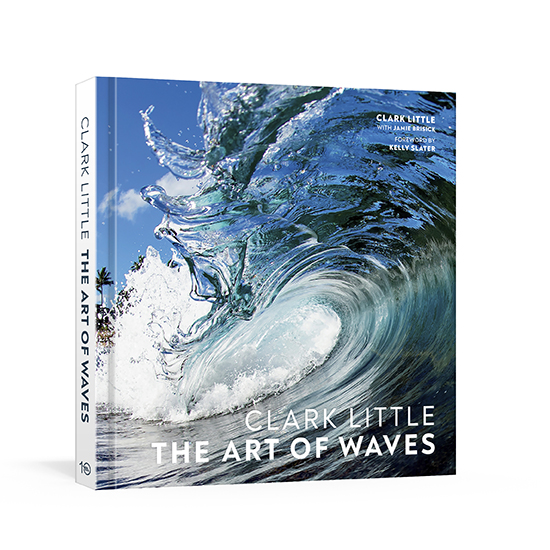

Clark Little made a splash in 2009 when he self-published “The Shorebreak Art of Clark Little.” The coffee-table book, with forewords from old friends Kelly Slater and Jack Johnson, visually chronicled his story from Northern California to the North Shore and his personal journey from shorebreak surfer, reckless four wheeler and botanical gardener to arguably one of the most famous ocean photographers in the world. Thirteen years later—after countless thrashings in the heavy Hawaiian shorebreak—Clark has saved some of his best work for his third, and perhaps final book, “The Art of Waves,” while also sharing some insights of his craft.

How did your latest, and perhaps final, book come about?

I hadn’t planned on publishing another book but the timing was right. My first two were self-published; it was a lot of work, and worth it, but I wasn’t going to do it again. An editor contacted me right after the Covid lockdowns with the concept for “The Art of Waves.” We’d been in contact for years, but this time something clicked. I hadn’t put out a book in six years, I had a lot of great shots sitting unpublished, including some of me shooting, and my team and I had the time to do it.

I specifically wanted the book to be available in Japan and Australia, two of my biggest fan bases outside the U.S., and through the publisher’s network it’s my first book available worldwide. I honestly don’t see myself making another book after this—at least that was the spirit I approached the project with.

How do you feel when you look back at your work?

Each book marked a different part of my career. When I look through the first one, I can see how I was just starting out in some shots, learning how to shoot shorebreak. It’s raw and experimental, yet some I consider excellent and are still popular in my gallery and as prints. It’s great to see they have aged well.

The new book is my best; I am really proud of it. I love the covers, image selection, sequencing, Kelly’s foreword, Jamie’s writing and how it captures the journey over the past 15 years. Two-thirds of the images have never been published in a book. My iconic shots, even a handful from my first book, made it in.

“The Art of Waves” feels more reflective and analytic, you share more about your process.

Yeah, part of the concept was to share my craft, give insights into unusual shots and have some short essays going deeper into waves, the North Shore and my life as a photographer.

For a long time I was trying to protect how I did things. Shooting waves was becoming popular; it was getting crowded on the beach. But I’ve let a lot of that go and decided I could share more of what I do. Hey, if everyone is having as much fun as I am shooting, that’s a great thing. We need more happy people in the world.

How has wave photography grown since you started?

There’s been a lot of growth. When the GoPro came out, it changed everything. Once the camera hit the market, you could buy it for a few hundred dollars and all kinds of people started showing up to the beaches shooting waves, their friends, taking selfies.

When I started, I would go to my local beach, travel to the outer islands, California or Japan and not see anyone shooting in the shorebreak. Then it boomed and people were doing it everywhere I went.

Have things changed much with your approach or routine?

Things have calmed down quite a bit. Instead of being in fifth gear and revving my engine hard, I feel like I am driving an automatic in cruise control. Still working hard and shooting all the time, but the pace is perfect. I also don’t go out and shoot in crazy big days any more. I love big waves, and still go out in waves that scare me, but I’ve pulled back from the death wish stuff a bit. A few too many close calls.

Those first few years I was racing around, so I was always thinking it would come to a stop any day and had to take advantage of all the opportunities. One week, I went to the Greenroom Festival in Yokohama for two days then jumped on a plane at midnight to get back to Hawaii to do the Today Show live on Waikiki Beach. Thirty-six hours later I was flying back to Japan to open an exhibit in Tokyo. I really like the pace now. Not as much adrenaline, but also not a blur.

Do you still go out and shoot solo?

Not much any more. One reason is I don’t wake up an hour before sunrise to get certain shots. I used to go out alone in the dark to catch the morning sun in the barrel. Now if I want those kind of shots, I go in the late afternoon and get the sunset in the barrel. Same shot, different angle and I get to sleep in.

When I started out I was alone at most beaches, even in the middle of the day. People would sometimes think I was drowning and go get help. They couldn’t imagine I was out there taking the poundings for fun. Now it seems everyone knows. No more false alarms for the lifeguards.

The last few years, when the waves and light are good, some of my friends come to the beach and its fun having everyone around hooting and hollering in the water. We push each other and share techniques. Tourists even show up and I sign some autographs. Social media and the GoPro changed everything. The secret is out and has been out for some time. I can choose to be grumpy about the crowds or embrace it and be stoked everyone’s having a good time. I choose to be stoked.

In the book, the anticipation of the impending wave is palpable in the shot “Flash.” What’s going through your mind at that moment?

I am in the zone. Time is slowing down. I am seeing what the wave is doing and aiming at the interesting parts unfolding, staying to the last possible second to get the critical shot while making sure I get through the wave unhurt, using my peripheral vision to see everything else that’s going on.

A lot is moving quickly at once, so I need to stay calm and slow it all down. The best shots are when I ride the fine line or cross it.

Are you still using a similar set up from when you started?

I had a cheap point and shoot with a case I bought on Amazon at first. When I pushed the shutter it would think, then autofocus. I could only get one shot at a time and had to time it just right. I would often miss shots.

Soon after seeing the potential with the point and shoot I got a professional Nikon D200 camera. Compared to that, my setup now is pretty similar. I shoot with a Nikon D5 and have a D4 as a backup. The technology has improved a lot. More memory, more shots per second, better quality.

One fun addition was mounting a GoPro to the top of my camera housing. The GoPro didn’t exist when I started and being able to film while I shoot stills adds a layer of fun to the process.

You need to ditch your camera sometimes on big waves. Many close calls with it flying around on the leash?

All the time. It’s one of the most dangerous things I have to watch out for. If that camera hits me hard in the wrong place, it can knock me out. I’ve had my head rung a few times and stitches to show for it. Some pretty close calls.

Are you often surprised after looking closely once you get out of the water?

A lot of shots surprise me when I see them at home on a screen. There are details that come out that I can’t see when I am shooting. Sometimes I know I got a good shot when I take it. “Rainbow Shave Ice,” I knew when I took it. Same with “Big Blue.”

The conditions can be optimal, yet if there’s a water droplet on my lens or if someone photo bombs me in the distance, I won’t know until I get home and see it on the screen. That’s when I know if I actually have something.

“Flying Honu,” which made its way into the Smithsonian, was one your first marine life photos. In the new book you dedicate a section to it.

Flying Honu is what got me started in the marine life shots. I used to shoot during summer or on small days in winter to stay in shape and get in the water. Once I got that shot, I really got into shooting and swimming with turtles.

Then I met some friends who took me out swimming with the sharks—cageless. It was pretty trippy for me since I grew up avoiding sharks when I surfed. There was fear, and when you first swim with them, the adrenaline is pumping. Then you learn more about them and get used to them. While out with the sharks, I might see whales, which led to whale photography. It wasn’t anything conscious; I like to stay active and keep things fresh, so I just embraced it.

You got out of your comfort zone shooting tiger sharks, how was the learning curve that first day?

It was wild, super crazy. Even the boat ride out took a bit to get comfortable. The crew I go out with—Juan Oliphant and Ocean Ramsey—are experts and taught me a lot. But you can’t let your guard down all the way. These are wild animals with powerful jaws.

Like surfers, you read tide and weather charts watching out for distant storms. Are you looking for the same patterns?

We are all basically looking for storms; none of us want it flat. But the good days at Pipeline might not be good at other beaches. Where I shoot, there is a sand bar that forms, shifts and changes all the time. Depending on the sand, I will look for certain swells. Some of my friends surf really big waves on the outside reefs. They are looking for a very different storm and swell. When the waves are that big, I shoot from shore and don’t go out. It’s suicidal and the lifeguards usually close the beaches.

Any plans to get back to Japan?

I would love to get back. I miss the people, the food, everything about it. Doing the Greenroom Festival every year was a lot of fun. Great memories from the exhibitions at Parco too. I want to take my wife and kids someday. I was happy I got to go to Japan with my mom before she passed away. She loved Japan and had many Japanese students (she was a professor in the Communications Department at the University of Hawaii).

Your son Dane scored the back cover; do you see him following in his dad’s footsteps?

He is good at it and seems to like it. He gets really close to the action too, but I’m not sure if he will follow in my steps. I don’t push him. Right now he’s into the plumeria farm his grandfather, my dad, started. He and I are spending the summer improving it.

You’ve mentioned the importance of understanding the physics of waves. Are you still learning?

Constantly learning. I have been studying waves since I was a kid, but there’s always something new keeping things interesting. Waves are dynamic. Throw in weather, wind, tide, clouds and sun into the equation and it gets more complex. My mind is blown all the time, it keeps me going out.

The Art of Waves (2022) is available in Japan through Amazon Japan and Kinokuniya Bookstores. Books Kinokuniya Tokyo (Takashimaya Times Square, Shibuya) has copies. You can also buy through ClarkLittle.com.