Japan’s newest national park, offers not only a look at one of Hokkaido’s less traveled regions, but also the Ainu culture and people, who have been in on the secret for centuries.

The long-term expat in Japan will often be asked their favorite place in Japan, and the answer is inevitably hard to come by. Hokkaido always appears at the tip of my tongue, but as it is less “Japanese” than the rest of the archipelago, it is never the answer I give. Yet, as I find myself gravitating there year after year to wander its peaks or to sink myself in its powder or hot baths, perhaps it is the answer I should give without hesitation.

Hokkaido’s foreignness stems partly from my seeing it as Japan’s Alaska, detached both geographically and culturally. Like America’s 49th state, it was historically linked with Russia, who never truly ceased their trading activities, despite Japan’s supposed 250-year sakkoku period of isolation. The shogunate established no more than a toe-hold on the island, and had no real control over activities beyond.

The rest of Hokkaido was the home of the Ainu, bolstered by their trade with Russia, and their familiarity with the land, whose natural abundance enabled them to live simple, yet sustainable lives. As is the sad case in most industrialized countries, the Ainu have been relegated to a few small pockets, known as kotan, where the old ways are encouraged, though in a far-scaled down version.

Many visitors to Hokkaido are familiar with Upopoy Kotan, due to its proximity to Sapporo, accompanied by a mild commercialization the proximity brings. I tend to prefer Akan Kotan on the far eastern part of the island, larger and more vibrant, yet with a vibe more like a small onsen resort. So it was a delight to visit Nibutani Kotan, with its small village feel, and its welcoming community.

I was in Hokkaido to explore Japan’s newest—and biggest—national park, the syllable-rich Hidakasanmyaku-Erimo-Tokachi National Park, designated just three weeks before. Nibutani lies amongst the Hidaka range’s western face, the forests and peaks above not only a source of sustenance, but the lair of the Kamuy, the gods whose worship give shape to the Ainu culture itself.

The day began with a ceremony traditionally undertaken before entering the forest. Our guide dipped an ornately-carved Ikupasuy prayer stick into a cup of sake, then three times flicked some drops onto a tree, an offering to the ancestors. We moved then through the forest beneath a mixed growth forest dominated by Katsura trees, which the Ainu see as sitting, their roots as legs underground. A powerful stream cut curves through the dense growth, making it easy to see why the Ainu wore leggings on their hunting forays.

The village itself was a short distance away, a collection of small wooden dwellings spread across a central grassy area. We paid a quick visit to Toru Kaizawa, hard at work at carving an incredibly detailed sheath for a hunting knife. His great grandfather had been one of the Meiji period’s best craftsmen, and Kaizawa himself is beginning to gain some renown overseas.

We were next given time to explore the cultural museum, divided into three zones, to the people, the land and the gods. In the former, the exhibits were organized from birth to death, each of the 1,121 items donated by Kayano Shigeru, the first Ainu politician in the Japanese Diet, and a leading figure in promoting its ethnic culture. A child of this village himself, the toys on display were all related to hunting, teaching them early essential skills.

The patterns on the traditional attire were an array of curls that looked almost Celtic. Originally made of bark fibers, cotton was introduced due to later trade. Today, the older bark clothing is still occasionally made, so as to honor tradition. It can require up to two years and seven kilometers of thread to make the outfit for a single male. The carvings were most remarkable, incredibly detailed shapes and patterns found on near every tool, utensils, and weapon. The heavy emphasis on sweeping curls led me to wonder whether they were inspired by blustery nighttime snow storms.

We regrouped at the largest dwelling at the center of the village, open and airy, with thatch from ceiling to floor. The eastern window was for the god to enter, as it faces upstream and Mt. Poroshiri beyond. Two windows to the south were for water and light to enter. A central fire pit was adorned with an iron pot, as well as drying racks. It not only heated the room but the thatch above, creating a form of insulation. The embers were cold on this midsummer’s day, as we sat around the pit to enjoy a lunch of traditional Ainu delicacies, namely salmon, vegetables collected from the local hills, and ohaw, a salmon soup, finishing with a millet and rice dish known as sipuskepmesi. A few of us took the opportunity to pleasantly doze under the temps of a perfect summer’s day, as an Ainu elder wove quietly in the corner.

At the village’s opposite end was the Kayano Shigeru Nibutani Ainu Museum, and we passed the afternoon in the cultural center next door, carving patterns onto small folding tables that we’d take with us for lunch in the mountains later in the week. Our visit to the village concluded with a brief stop to try our hand at playing the tonkori, a type of five stringed, un-fretted lute. Played cradled against one shoulder like holding a baby, its rhythmic tone is deceptively soothing. But, in the hands of famous performer Oki, it is something else altogether, as can be seen in any performance of his Oki Dub Ainu Band.

In the morning, I watched the sunrise over the Hidaka range’s peaks, whose centerpiece, Mt. Poroshiri, is listed on the 1964 bucket list known as the Hyakumeizan, orJapan’s 100 Eminent Mountains. We didn’t have the three days needed to check it off our lists, but we would climb Mt. Apoi, further down the range, which rises directly from the Pacific, enabling an attractive sea-to-summit traverse.

The night before the climb, we prepared the ingredients for the day’s picnic, namely rice. spice, and sliced sculpin rockfish, which must surely be one of the world’s ugliest fish. Our labors packed away in vacuum sealed bags, we tucked into an immense feast of sashimi sliced from the abundantly rich cold waters a few blocks away. There was the familiar salmon, Alaskan pollock, and squid, plus a regional type of monkfish meal known as tomoae. The night, while lively, but didn’t last long. We had a mountain to climb in the morning.

The sea off our base in Samani town was rich in kelp, an industry dating from the time of the Ainu, who had a small community here, endeavoring to maintain their language and culture. Their familiarity with the waters was apparent from local legends, namely the towering rocks offshore, identified as a retreating chief and his wife and child, frozen in time in order to elude capture.

The hike began just uphill at the Apoi Geopark Center. Our guide Tanaka-san led us past the obligatory bear warning sign, to an array of small concrete pools now filled with a variety of plants local to the mountain. The botanist overseeing the place had long ago replaced the herpetologist who once collected mamushi (pit vipers) here in order to extract their venom for medicine, or to pickle their bodies to make local firewater.

The trail shaded by red pine was rife with deer tracks, and the mangled wooden signage raked with higuma claws. Though attacks were rare, the higuma is one of the world’s largest species of grizzly, and the damage they’d done to the signs was impressive. To the Ainu, they were the greatest of Kamuy, and must have been the most terrifying of gods. I’d hate to run into one camouflaged by the rhododendron climbing high in order to find sunlight. Round rocks here and there indicated the presence of an ancient river.

Hokkaido trails tend to be incredibly long, distances dictated by lengthy traverses through dense forest and creeping pine, which lead to the foot of the mountain itself. But what made this trail unique was that we were literally traipsing over the earth’s mantle, driven upward by a violent collision of tectonic plates, with this very peak a by-product. A literal journey to the center of the Earth.

These rocks formed the spine of a steep climb, which dog-legged into a long ridgeline that, aside from the odd rock scramble, gradually led to the peak. The name Apoi comes from the Ainu language, meaning “place of fire,” after the bonfires the Ainu had lit on the summit as a means of asking the gods to bring them deer, whose populations had diminished. We had our own fires to attend to, heating the meals that we’d prepared the night before. The views were surprisingly clear, a long entire stretch of shoreline beneath the bluest of skies, the trail below alive with families with small children, or old timers collecting summits.

Partway down, I passed a trail heading deeper into this brand new national park. So tempting to take it, to cross the whole of Hokkaido itself over the long line of volcanoes that the Ainu had called Kamuy Mintara or Garden of the Gods. But that will require yet another journey, to dive deeper into Hokkaido’s seeming endless riches, and into why the Ainu had called it home.

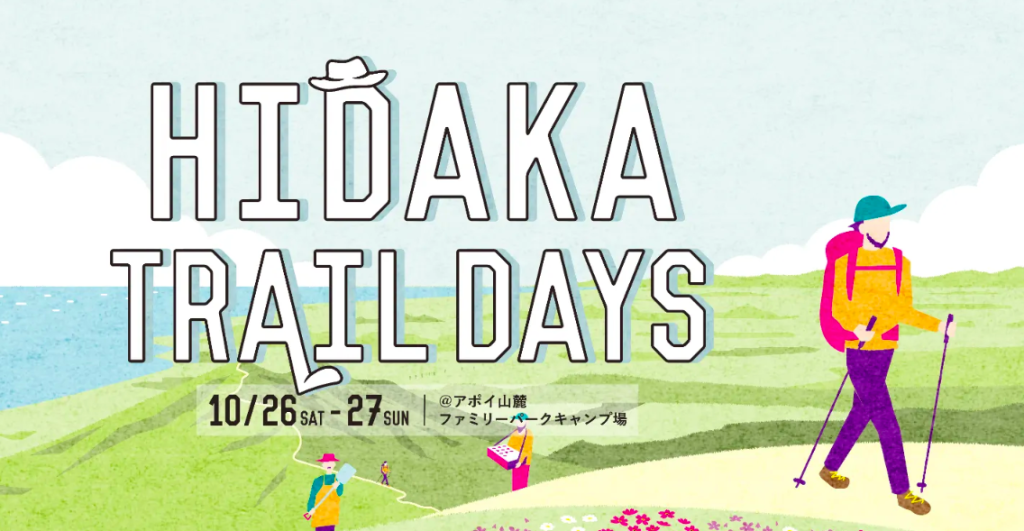

HIDAKA TRAIL DAYS

Travelers, outdoor enthusiasts and gearheads won’t want to miss Hidaka Trail Days, where adventure meets the stunning wilderness of Hokkaido! From hiking breathtaking trails to enjoying local food to dozens of small outdoor brands and inspiring talk shows, this special two-day event takes place October 26-27, 2024. It’s the perfect autumn escape into nature’s beauty. For more information visit hidakatraildays.com.