“You’re a fool if you don’t climb Mt. Fuji once, but an even greater fool if you climb it more than once.” To rephrase this famous quote, anyone who has not climbed the 3,776 meters to the peak of Japan’s tallest mountain is a pitiful creature. And if you’ve gone through the unexpectedly difficult task and then decided to go back and do it again, you are an idiot.

If this is true, there is no bigger idiot than my older brother Takeharu. If you look at the characters in his name, “take” means a tall mountain, while “haru” means a clear blue sky. My parents must have known something, because for 20 years he’s been working in a hut at the top of Mt Fuji.

The hut sells kokuin, the seals people stamp on their wooden climbing sticks, and souvenirs, and during the peak month of the climbing season, he’ll stay up there the whole time. It’s a lifestyle of looking down on the rest of the earth, feeling the strong sun beat down on your skin, of having the wind suddenly blow away obstructing clouds giving you that special sense you get only in high places of being close to heaven.

My parents named me Mitsuharu; michi means high tide, haru again is that open blue sky. I’m a photographer of the ocean, waves and surfers, and for 15 years have made my living on a southern island as a fisherman.

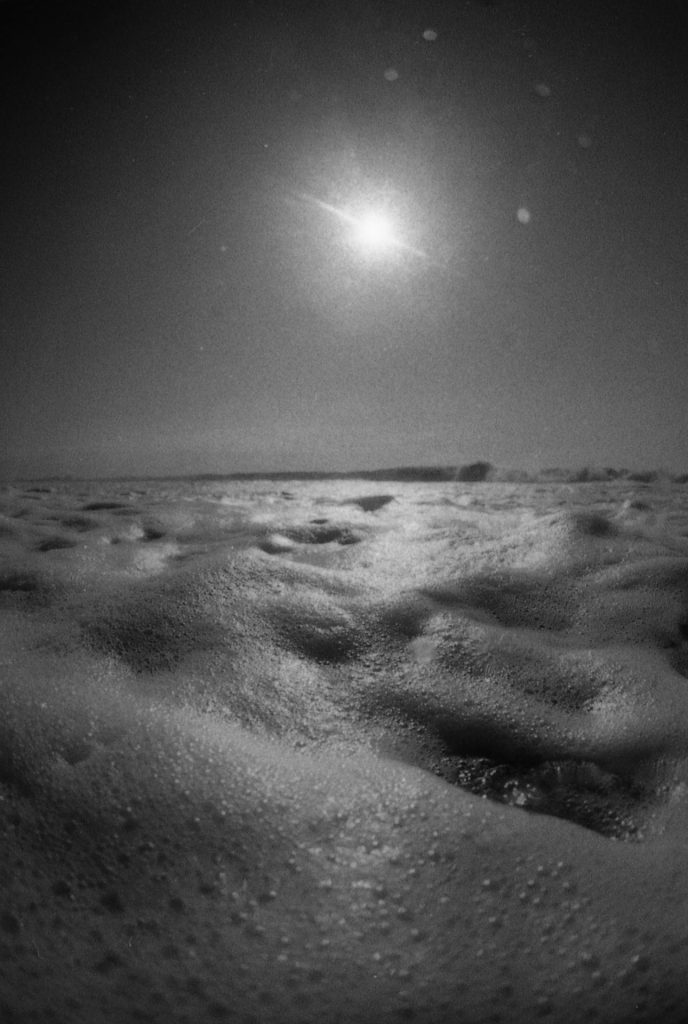

A mountain man and an ocean man, brothers. Yet, I discovered there is something in clouds that brings us together. My brother took a photograph and on it wrote “unkai,” un for clouds and kai for sea, referring to the phenomenon of being at the top of a mountain and looking down onto a sea of clouds stretching to the horizon like the vast ocean. It’s a magical photo.

I, on the other hand, like to float on the water with just the tip of my fisheye lens breaking the water’s surface and shoot the sky.

One brother looks down at the clouds from the highest point in Japan while the other is at the lowest point looking up at them. Looking down or looking up, lately I’ve been thinking about this.

I’ve been working in a facility for mentally challenged people producing bio-diesel from used tempura oil. During the process of collecting “waste oil”—the material thrown away by people—I’ve experienced the kindness of people, as well as been looked down upon.

“People treat us like garbage, too,” one of my co-workers said. “But we should try to stay positive.” His words have very gradually made an impression on me.

When I’ve gone to take photographs of prime ministers or members of the Diet, I find people are always flattering them. So, even if they have good intentions, they are always looking down on everyone. I’ve concluded it’s not a good thing for people to look up or down at each other. And we’re not the only ones looking up at the sky; all the creatures in the natural world do too.