For years I’d wanted to hike the Nakasendo, the ancient Edo Period route used for travel between the capital of Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto. The 69 post towns along the Nakasendo provided accommodation and services to daimyo (feudal lords) and their entourages on their sankin kotai (biennial visits) to the Tokugawa Shogunate from 1635 to 1862. The road also catered to travelers keen to follow in their footsteps.

The most popular and picturesque section of the famed byway is the lower Kiso Road from the post town of Magome-juku to Tsumago-juku. This seven-kilometer stretch starts in Gifu Prefecture and ends in Nagano Prefecture. It is short but the best-preserved section of the Nakasendo. Since it is an easy day hike and the trails are in such good shape, I chose to jog it.

It is well known that Matsuo Basho wandered the Nakasendo but it is Magome’s native son, Tosan Shimazaki (1872-1943) who is inextricably linked to this section of the Kiso Road. The Shimazaki family served as the village headmen, housing the feudal lords and pilgrims such as Basho when they passed through.

In Magome-juku, the atmosphere is thick with the dubiety of the novelist and progenitor of modern Japanese poetry. A celebrated but controversial figure, Shimazaki fled to France soon after impregnating his niece. Don’t miss the Shimazaki museum located on the main cobblestoned road through town.

Arriving in late afternoon, I saw Mt. Ena (2,191 meters) looming, casting long shadows over the countryside. I trudged up the very steep and cobbled main road to Eishoji, a Zen Temple accommodation serving shojin ryori (vegetarian food). This temple, under the former name of Manpukuji was featured in Shimazaki’s tome “Before the Dawn.” (Yoakemae 夜明け前 in Japanese)

In a formal tatami mat room facing a garden populated with lounging cats, a dozen bowls and plates of food were set out for me on the table. I felt immediate conflict when I noticed that the scroll overshadowing me from the tokonoma (alcove) conveyed the kanji for “patience.”

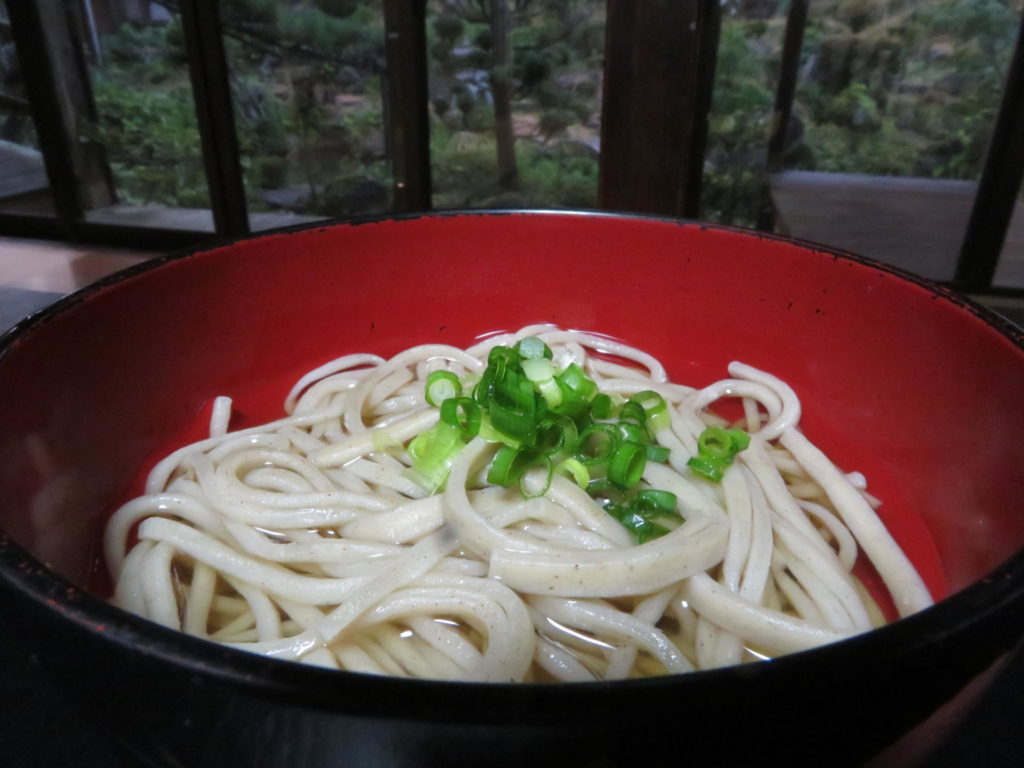

The temple priest’s wife explained the dishes: ganmadoki (fried tofu made with shaved lotus root and potato), a bowl of fresh tofu in a light sauce, a square of sesame tofu with a drip of wasabi on top, steamed green vegetables, boiled pumpkin artfully arranged in a blue-sided dish, a sweet red plum, eggplant boiled to a sheen and graced with miso sauce, cucumber salad, soba noodles, a generous bowl of raw pink ginger and locally harvested rice. Plus tea, of course. She politely bowed, left the room, and I dug in, completely ignoring the ancient scroll’s advice.

In the morning, after a waltz around thee temple graveyard and a visit to the Shimazaki family grave, I left the peaceful temple grounds of birdsong and pathways laced with moss and continued up the steep Magome hill towards the trail. I procured individually wrapped kurikinton— candied chestnuts from a confectionary run by a toothsome dowager who said she had lived in this village her whole life.

At the top of the path, I glanced back at Mt. Ena and the Mino Valley before padding across the ishitatami, the inlaid stone indicative of the ancient Kiso Road.

At the entry to each section of trail there are “bear bells” numbered in descending order as I traveled in the direction from Kyoto to Edo. Ringing each bell is said to scare away any bears from the path. There’s an English sign at each bell station that says, “Ring the bell hard against bears!” It sounds like a campaign, “Just say no to bears!”

The well-preserved trail offers tea houses, rest spots, toilets and water at regular intervals. After 5.5 kilometers, the route crosses into Nagano Prefecture and the Magome Pass (801 meters) winds down into the next post town of Otsumago. The trail surface in this section (crushed rock, scree, gravel) partially follows a stream, the path hopscotching from one side of the brook to the other via wooden pedestrian bridges. This is absolute heaven! Later, you can stop at the Otake and Metaki waterfalls (“man” and “woman” waterfalls) and even treat yourself to a dip in the swimming hole beneath Otake.

Before descending into Otsumago, I came across “Gyuto Kannon” a stone tablet monument to the black cattle who carried the heavy loads across the pass in the old days. This is special because most of such shrines across Japan are for horses. I added a coin offering to show homage to the bovine ancestors of Japan.

In Otsumago, a town the size of a handful of rice, I found houses perched on the edge of a stream. Every domicile featured a whispering furin (wind chimes), handmade from a five-yen coin and a bell dangling inside a pet bottle. Work gloves hung out to dry, fire wood stacked in cords outside and weed cutters sat at the ready. It’s the Japan everyone wishes still was.

Golden rice fields begged to be harvested as I descended into the hamlet of Tsumago-juku. Propped open doors of row houses allowed an inside gander at Japanese life still lived in today’s countryside. A lazy dog lying in the doorway lifted one sleepy eye to note this stranger running past. Small shops purveyed souvenirs and wooden toys and elderly women painstakingly wove straw-coned hats from hinoki (Japanese cypress) to sell to tourists. Rows of soba shops that had previously fed the legions of attendants to the daimyo during the Edo Period now served their replacements: bus tourists streaming in by the hundreds.

A tall man with a friendly smile hailed me from the open doors of a latticed wooden house. “Oyaki!” he hollered, referring to the hot buns filled with delectable vegetables and sweet walnut paste. Mr. Hara has been selling oyaki from his shop since he returned to his hometown 26 years ago. This retiree was imbued with a new- found energy he surely never had in his youth.

Although the Magome-Tsumago hike is short, there is much to do in each post town. I put my sites on sampling the Jurokudai Kuroemon sake at a quiet shop facing the old road. Sitting on the porch, I imbibed with my companion, a small toy horse made from cherry wood and easily imagined daimyo processions passing through town. Perhaps the sake invigorated me because after this short rest I yearned to go a little further that day.

I hiked another five kilometers to Nagiso Station in Midono along a narrow paved road that wandering drunkenly among small country houses and rice fields. Lichen-covered monolith stones along the way entertain pilgrims with inscriptions and haiku poems providing yet another distinct treat along the lower Kiso Road.

At the end of my 15-km. day on the Nakasedo, the sun was setting and I could no longer see Mt. Etna. But I discovered a different kind of mountain in front of Nagiso Station— matcha azuki kakigori served at the cafe across the street. I set out to conquer it immediately. Both Shimazaki and Basho surely would have, at times, taken part in this ancient treat.

Getting There

By Train: From Nagoya Station, transfer to the Shinamano Limited Express train to Nakatsugawa Station. (50-min.) From Nakatsugawa, take a 30-min. bus. To get to Nagiso Station, transfer at Nakatsugawa Station. From Nagiso, take a short taxi or a bus to Tsumago.

By Bus: Highway buses between Shinjuku and Nagoya stop at the Chuodo Magome Bus Stop. Magome is a 20-min. walk from the bus stop.