Walking through a damp, faint trail along a rice paddy, long curly grey locks peak out around the corner of a room where stacks of novels, magazines, and art supplies surround an out-of-place, shiny silver Mac computer. Illustrator, puppeteer and long-time Sado resident Johnny Wales waves me over to his studio, then leads me to a building a few feet away. As the door to the traditional Sado-style farmhouse slides open, Kyla, Johnny’s Akita dog, greets me enthusiastically before falling into a lazy slumber by the old shoyu barrels in the covered corner of the outdoor hall.

“My wife and I bought this home three years ago from a 101-year-old man. The house is just as old as him,” Wales says while pouring piping hot coffee into mismatched mugs, “We replaced the tacky tiles in the kitchen with older, dark wooden flooring from a friend’s home that was getting demolished.”

The creaking kitchen floors remind me of the scene from “My Neighbor Totoro” where Mei and Satsuki run up and down the old dusty home, cleaning the floors just like those here. Retro signs of salt, coffee and the like hang from the walls at no particular height or placement. They look as if they were taken from stores that closed down one by one as populations outside large cities dwindled.

Wales talks as he strolls through the dim rooms in his proud home, flicking on lights and opening windows here and there as we enter a large room.

“The main room is the same size as a Noh stage, with two rooms next to this the same size. That’s how all Sado-style farmhouses were made back in the day. The size of three Noh stages is the rule. As it should be! A family home was the center stage for all events in life and for a family. Weddings to funerals were all held in these rooms.”

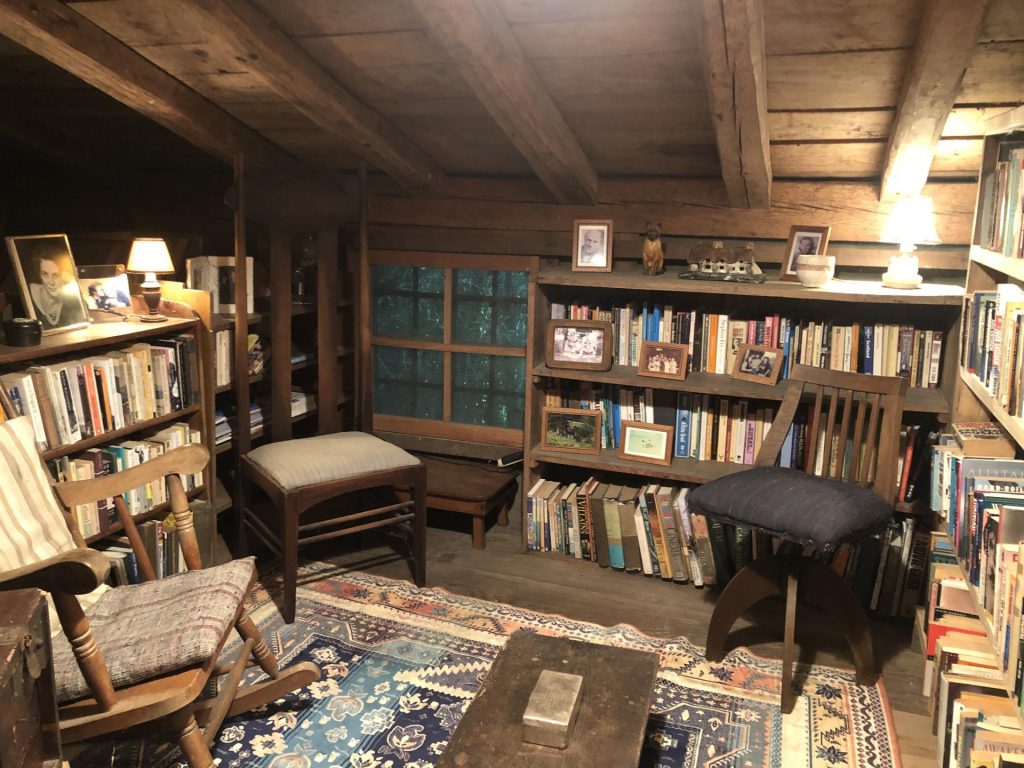

Retracing our footsteps through the house along the outer hallway we somehow end up in yet another room, a museum of sorts storing Wales’ collection of everything imaginable from classic car figures to Japanese brush and ink holders that “everyone mistakes for pipes,” he notes, a doll house, a 3-D replica of a Van Gogh painting and puppets–all handmade by Wales. On the walls hang newspaper clippings.

Settling into the cozy worn-in chairs in his studio, he tells of how he fell in love with Sado, and how it continues to surprise him with new joy every day.

“Sado was the Japan of my dreams,” Wales reminisces about his first visit to Japan in 1975 on a three-week youth exchange. “Just as I thought about skipping out on the last few days of planned tours, we visited Sado Island and it felt like I was lifting up a curtain revealing the Edo Period.”

Even after returning to Canada, he knew he needed to find a way back to Sado. As an artist, he was well versed in theater and various arts. He recognized and appreciated the passion Sado’s artists and musicians displayed sharing their own creative vision with people considered “outside” of the community.

“Sado’s uniqueness is in the strong belief of participatory culture,” he raves. “Go to the museum and you’ll find signs that read ‘Please touch the objects.’ Elder artists will hand over their art supplies and tell you to give it a try. I’ve never seen that in big cities where, if you belong to a community of artists, you’re part of that community, but no one from the outside is allowed in.”

After working with Kodo on production and lighting on their North America tour, Wales returned to Sado in 1977 to work as a puppeteer under master Moritaro Hamada while living in a cabin by the sea in Shimafumi on Sado’s southwest coast.

“An old lady rented out a cabin to me for ¥1,500 a month,” I pause to calculate, believing he means dollars. “I know what you’re thinking,” he adds, noticing my expression.” It really was yen. I did the math over and over again too, and with the exchange rate then, it came to about four Canadian dollars a month.”

The puppeteering stint only lasted 14 months, admitting to the pressure and struggles he felt as the only foreigner on the island back then. “I felt like a star and a freak at that time. Sado was way too small of a stage at that time.”

Wales returned to Sado in 2000 with his wife. He was able to work remotely as an illustrator for Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun, thanks to the internet boom at the time. Although she is from Tokyo, she found solace on the island. “Sado isn’t right for everyone, we’ve both been around the world, but it’s right for both of us, then and now.”

Sado harmoniously blends a varied landscape of nature and people. The affordable cost of living and the fresh and delicious seafood add to the richness of the island. Wales believes that Sado isn’t just another inaka countryside region in Japan. Its artistic history and wealth deposited by the gold mines cultivated deeper investment and roots in preserving and providing the unique culture and arts on the island.

“Everyone here is welcoming—that’s part of the culture. And if you come here to live or visit, you’re expected to participate in any and all aspects of it,” he adds.

The island isn’t small: it takes nearly half a day to drive around so plenty to explore. Wales, who’s been a resident of Sado for nearly half a century, says he is still discovering Sado, much as he did in his youth. He notes there are new rivers and streams when the ever-changing coastlines recede. Sado also hosts the world’s smallest hanabi taikai (fireworks festival) in Osaki.

Many long-term residents hope to see more of the arts and lifestyle being supported through new generations moving over. A good example is Kodo, as their extensive apprenticeship program attracts passionate taiko drummers from all over Japan and the world. Yet Kodo isn’t the only creative passage onto the island, especially for remote creatives like Wales himself.

GETTING THERE

Sado Island has three ports easily accessible from Niigata City. As access is difficult without a car on the island, Sado Kisen operates several car ferries and high-speed jetfoils throughout the day. As the Sea of Japan can get rough, especially during the winter and typhoon months, be sure to check ahead as ferries can get cancelled.

From Niigata to Ryotsu: The car ferry takes just over two hours and costs about ¥2,510 while the high-speed jet foil takes one hour and costs ¥6,520.

From Naoetsu to Ogi Port: Sado Kisen operates one to three car ferries per day to Ogi Port. The one-way journey takes just over two hours and costs ¥2,720. This ferry does not operate from late November to February.

From Teradomari to Akadomari: Sado Kisen operates one to three high-speed boats to Akadomari. The one-way journey takes one hour and costs ¥2,960. This ferry does not operate from December to February.